Originally published at The Gospel Coalition Canada on May 1, 2018. (2nd of 3 parts on the Canadian Church and the public sphere) (pt 1)

TGC Editors’ note: Canadian Evangelicals have largely lost their voice in the public sphere of Canada. It hasn’t always been this way. The pathway toward a distinctively Canadian secularism is an interesting story. Regaining some of what was lost will require us to understand that story and then to move forward in humble and yet decisive engagement in a country that has lost its way. There is almost none better suited for this task than Don Hutchinson, a man who has an intimate knowledge of the rise of Canadian secularism and the nature of religious freedom in our land. This article is part II of III (here is part I).

For the Dominion of Canada, the twentieth was a century of promise and fulfillment, challenge and response. The century would be nearly done – 1982 – before the nation would complete its quest for independence. In that time more than two dozen constitutional amendments were sought from the British Parliament at Westminster.

As the century started, there was rapid expansion from Atlantic to Arctic to Pacific in population, nationwide transportation networks, and the recognition of new provinces and territories. But even as the young nation asserted itself in North America, the decision to send Canadian troops to fight in Europe’s Great War was made in Westminster’s Parliament, not Ottawa.

On the battlefield, first at Ypres, then Vimy and others, Canada’s troops distinguished themselves as a formidable national fighting force. Congratulatory messages were sent to Prime Minister Robert Borden rather than his counterpart in London. The Canadians had won an identity of their own.

Soldiers came home in victory, despite the loss of nearly 61,000 Canadian lives. Canada’s churches strengthened with the post-war celebration, comforted those who lost loved ones and welcomed the influx of European immigration that followed.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s congregations and para-congregational missions were the backbone of voluntary and government networks meeting human need. The federal government extended the Income War Tax Act of 1917, initially a temporary measure, adding to it a deduction up to ten percent from taxable income for donations to charitable organizations such as churches and missions.

The trauma of the Depression reshaped Canadian politics. The prairies gave birth to the Social Credit Party and the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, both led by ordained Christian ministers. Social Credit’s “Bible Bill” Aberhart, a Baptist, became premier in Alberta in 1935 (succeeded by evangelist Ernest Manning from 1943 to 1968). J.S. Woodsworth, a Methodist minister, was a leader in the social gospel movement and led the CCF into Parliament. Tommy Douglas, a Baptist minister, led the first socialist (CCF) government in Canada when elected premier of Saskatchewan in 1944. In 1961 Douglas stepped aside from premiership to become leader of the federal party at the convention when it changed its name to the NDP.

World War II was different from the Great War (WWI). Canada’s Parliament declared the nation to be at war seven days after the British Parliament. Ottawa was still obliged to follow the lead of Westminster, but this was a symbolic but significant gesture of independence. Over one million Canadians distinguished themselves in service during WWII on the ground, in the air and on the sea.

The end of the century’s second war, however, produced a sense of uncertainty. Radio had brought the realities of war into the living rooms of the nation, and video into its movie theatres. Combat in the air and on the sea made the world smaller. Some enemy vessels had even made it to Canadian waters. And the development of atomic weapons spawned duck and cover drills in schools.

The Depression had outstripped the church’s capacity. The social gospel response of church-leaders-turned-political leaders encouraged the government to take greater responsibility. Uncertainty following WWII undermined confidence in the church and its God. This marked the beginning of the Canadian trend toward bigger government and smaller churches.

The Roman Catholic Church in Quebec was caught in a maelstrom brought on by Depression, WWII and its close affinity with the corrupt Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis, defeated shortly after his 1959 death. La Revolution tranquille (“the Quiet Revolution”) brought cultural and political change to Quebec.

The arrival of the “three wise men” from that province signaled a tide change in federal politics. Newly elected Liberal Members of Parliament Jean Marchand, Gérard Pelletier and Pierre Trudeau joined the government and cabinet of Lester Pearson in 1965.

Also in 1965, Pierre Berton’s The Comfortable Pew: A critical look at the Church in the New Age was a bestseller. The Anglican, United, and Presbyterian churches accepted former-Christian Berton’s opinion that they needed to step away from the Gospel, toward greater cultural alignment and social engagement.

Ten Protestant denominations had joined together in 1944 to establish the ecumenical Canadian Council of Churches. Over time they were joined by Orthodox and Catholic denominations. Most evangelical denominations avoided this early ecumenical movement, having retreated into a focus on worship and evangelism. But in 1964, a group of leaders concerned about cultural drift away from biblical principles formed The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada as a place to build relationships and discuss their concerns.

Canadian society was in a state of flux. The elements of politics, culture, and the church – churches – were on a variety of disparate paths, all leading to collision in the public square. Some would entertain conversation at the nexus. Others would engage in criticism and censure.

Pearson, managing a minority government following the elections of 1963 and 1965, was obliged to Douglas to keep his government alive. Douglas’ influence resulted in government implementation of national plans for health care, pensions, and student loans.

Trudeau, a lawyer and intellectual Catholic, became Pearson’s Justice Minister. Influenced by concepts of individual rights from the writings of French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, who worked alongside Canadian John Peters Humphrey in drafting the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Trudeau would begin to re-focus the law on the individual’s desires instead of the historic, biblically-informed, interests of the broader society. He introduced legislation that provided for no-fault divorce, qualified surgical abortion, and the decriminalization of homosexual sexual activity between adults, famously declaring “there’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.”

Following Centennial celebrations in 1967, in 1968 Trudeau succeeded Pearson as Prime Minister. He was quick to initiate pursuit of a constitutional bill of rights as part of bringing the Canadian constitution under Canadian control. A 1971 effort gave Ontario and Quebec each a veto. Quebec’s premier, Robert Bourassa, exercised it. Trudeau would not repeat that mistake in the next round of negotiations. A decade later, following the near constitutional crisis of the failed 1980 Quebec referendum on separation, all provinces except Quebec sided with Trudeau.

On the steps outside of Canada’s Parliament, on April 17, 1982, Prime Minister Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II signed the Constitution Act, 1982. Canada’s constitution was home. The British North America Act was renamed the Constitution Act, 1867. And the nation had a Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The Charter would change the Canadian legal system and influence the already shifting relationships between state, culture, church, and Canadians. The independence of a nation was established. The Charter became the foundation for a society whose citizens would become more focused on personal independence, individual rights, and private benefit than on the broader cultural and societal Canadian good. And much of the church offered little to counter that transition.

In its first decision on the Charter right to “freedom of religion” the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a “truly free society is one which can accommodate a wide variety of beliefs” and that freedom of religion was “the right to entertain such religious beliefs as a person chooses, the right to declare religious beliefs openly and without fear of hindrance or reprisal, and the right to manifest religious belief by worship and practice or by teaching and dissemination.” A Canadian, the Court ruled, was “free to hold and to manifest whatever beliefs and opinions his or her conscience dictates, provided inter alia only that such manifestations do not injure his or her neighbours or their parallel rights to hold and manifest beliefs and opinions of their own.”

Adjudicated in the context of a commercial dispute by a pharmacy that wanted to remain open on Sundays, that first case, R v Big M Drug Mart, established that government cannot support one religion over another and each Canadian is free to decide what he or she does or does not believe. This judicially-enforced personal autonomy has led to considerable litigation, particularly concerning disputes between individuals, organized religion and government, including undertakings such as education and marriage.

The independence of the nation by the beginning of the twenty-first century and a citizenship that embraced Charter assured individualism ushered in what Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor termed “a secular age.”

The expressed desires of individuals often shouted down existing societal requirements. Politics became increasingly challenging and polarized. Growing numbers of Canadians began to identify as having either no religion or a self-determined spirituality. Those occupying pews on a Sunday morning decreased in number. Church buildings that were raised in an era of booming congregational growth survived as heritage sites, community centres or live-performance theatres. Even for Christian Canadians, congregational connection started to shift from traditional churches in which birth led to membership to those more focused on personal choice to follow Christ, perhaps a policy that better fit with the new individualism. Great Britain faced similar societal change and challenges but was no longer the arbiter of the Canadian response. The response was determinedly in Canadian hands.

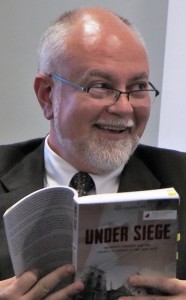

Don Hutchinson has held leadership positions within the Canadian Church for over three decades. He has served in the roles of pastor, lawyer and consultant, as well as in government relations. Don is the principal of ansero, a ministry facilitating partnerships for those engaged on the issue of religious freedom in Canada and with the global persecuted Church. His book Under Siege: Religious Freedom and the Church in Canada at 150 (1867–2017) has been recently released. Purchase it here.